When the Sun Won’t Shine

- Soil Fertility Services Ltd

- Nov 10, 2025

- 3 min read

What the UK’s dullest October in 60 years means for farmers.

October didn’t arrive with a dramatic headline. No endless rain drowning drilling plans. No surprise frost wiping out late crops. But in farming, the problems that sneak in quietly can be the most disruptive. The Met Office has confirmed that the UK recorded just 63.3 hours of sunshine, the third-dullest October since 1910, and that lack of light may carry more consequences than many realise.

Sunlight is the currency of crop growth. Every hour of brightness turns water and nutrients into biomass, roots, energy reserves and yield potential. In short: sunshine pays the bills. This October, crops were given a much smaller paycheque.

Many autumn-sown cereals have entered winter looking tired, establishing, yes, but not thriving. Tillering has slowed, roots remain shorter in soils that need depth and resilience, and plants are drawing on reserves rather than building them. Later-drilled fields, already behind schedule, have had their margins squeezed even further. OSR that looked strong in September has, in some cases, stalled, leaving patches vulnerable to pigeons and disease.

Root crops tell a similar story. Carrots and potatoes typically rely on October to pack on weight and sugars. However, with the lights effectively dimmed, dry matter accumulation has eased. For growers pushing late lifts, that may mean more variability in both marketable yield and storability, a headache that remains hidden until grading day.

Cover crops, today’s soil armour and tomorrow’s nitrogen cycle have also struggled to build the canopy needed before winter. The principle is simple: the more sunlight a crop receives in autumn, the more biomass it creates and the more roots it sends into the soil. Without energy, many mixes have grown half of what they might in a brighter year. That means less soil protection, fewer living roots feeding microbes, and more potential for leaching and compaction as winter rain arrives.

Below ground, the microbial workforce has also been put on a restricted diet. Soil biology depends on the carbon plants pump into the root zone. When crops slow, exudation slows. Residue breakdown lags. Nutrients remain locked up in straw and stalks rather than being cycled into availability. Many fields that were expected to be “clean” by now still show stubborn residues that will make spring drilling trickier, especially if the weather turns sticky.

And it isn’t just about biology. When sunlight falls short and soils stay cool and damp, the scales tip in favour of pests and disease. Slugs are more confident when plant vigour is low. Mildew and stem-based diseases thrive when plants lack the strength to resist infection. Those thin, pale patches we’ve all seen from the gateway often become hotspots of yield drag later on.

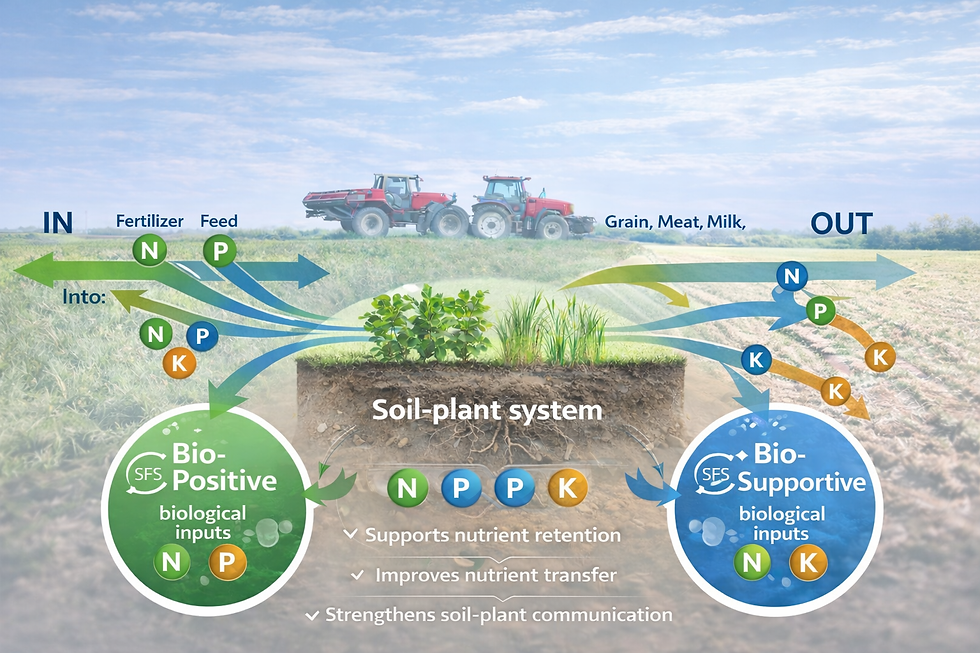

So what do we do about an October like this? We plan. We adapt. And importantly, we don’t assume the crop will simply make up for lost ground in spring, because recovery depends on what’s happening now beneath the surface. Supporting the root–microbe partnership becomes critical. Helping soils continue to cycle nutrients even while plants are idle makes the system more resilient. Residue decomposition, stress buffering, and soil structure improvement aren’t “nice to haves” — they’re the difference between crops that survive winter and crops that take winter in their stride.

There’s also a larger pattern emerging here. Our industry has become accustomed to measuring extremes: rainfall records are broken, heatwaves are becoming normal, and floods are turning headlines into frustration. But sunlight is one of the most critical limiting factors in UK agriculture, and one of the least discussed. If this year is a hint of a climate trend where “dim” autumns reappear more often, then the farming systems that value healthy soils, strong biology, and efficient nutrient use will hold a clear advantage.

Nobody will remember October 2025 because it looked unremarkable. But crops will remember it in March. Soils will remember it when we pull drills out of the shed. And businesses will remember it when the yield map shows where establishment never truly got going.

October simply lowered the lights on a job that still needed doing. The question now is whether our soils and crops have enough resilience built in to keep the engine running — even in the dark.

Don’t leave the impact of a dull autumn to guesswork. If you’d like to assess where your soils and crops stand — and what they need to hit spring running — get in touch. SFS is here to help.

Comments