The Nitrogen Trap: Why So Many Crop Problems Start Before We Even Open the Bag

- Soil Fertility Services Ltd

- Nov 17, 2025

- 3 min read

Every winter meeting eventually circles back to the topic of nitrogen. It’s always the same conversation: rates, timing, prices, “what did you do last year?”, and a general sense that nitrogen is both the hero and villain of modern farming. The truth is that nitrogen isn’t the issue at all; the problem lies in how easily we misuse it, and how far we’ve drifted from understanding the soil system that’s supposed to hold and manage it for us.

Nitrogen provides an immediate visual response, encouraging a specific mindset. When a bit works, it’s tempting to think that a bit more will work even better. The trouble is that crops respond very differently once nitrogen tips from “useful” to “unbalanced.” Excess nitrogen doesn’t create a more vigorous plant; it makes a larger, softer, more watery one. Those plants look impressive from the road, but they lack density, structure and resilience. It’s the agronomic equivalent of pumping air into a balloon and calling it muscle.

Once the plant becomes watery and poorly balanced, it emits the exact signals that insects are designed to detect. Research work has shown that crops emit infrared patterns based on their nutritional status. When nitrogen overwhelms the plant’s chemistry, that signal becomes jagged and erratic, and insects home in on it with remarkable accuracy. In other words, weak plants attract pests, and unbalanced nitrogen is one of the main reasons why a crop can look healthy yet remain a magnet for trouble.

All of this is made worse by the fact that our soils can no longer hold excess nitrogen in the way they once could. The stable storage pool for nitrogen is humus, and we’ve burned through a massive proportion of it over the last century. Without sufficient humus, nitrogen has nowhere safe to sit. If the crop doesn’t grab it immediately, it either disappears into the atmosphere or finds its way into the nearest ditch. We pay for it twice: once when we buy it, and again when the soil fails to retain it.

It’s worth asking how we ended up in such a simplistic nitrogen-fixated system. A century ago, some very clever chemists burned plant tissue, analysed the ash, identified nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium as the main components, and concluded that these three were essential. Everything else— organic matter, biology, carbon, trace elements, and slow mineral cycles — got pushed aside. We removed a full spectrum of nutrients with every harvest, but only replaced three elements, and unsurprisingly, plant immune systems weakened. Pest and disease pressure rose, and instead of reconsidering their approach, agriculture doubled down with more chemical use. Each year since, the global trend has remained the same: more pesticides and fungicides are applied, yet more pest and disease pressure is observed. It’s a treadmill, not a strategy.

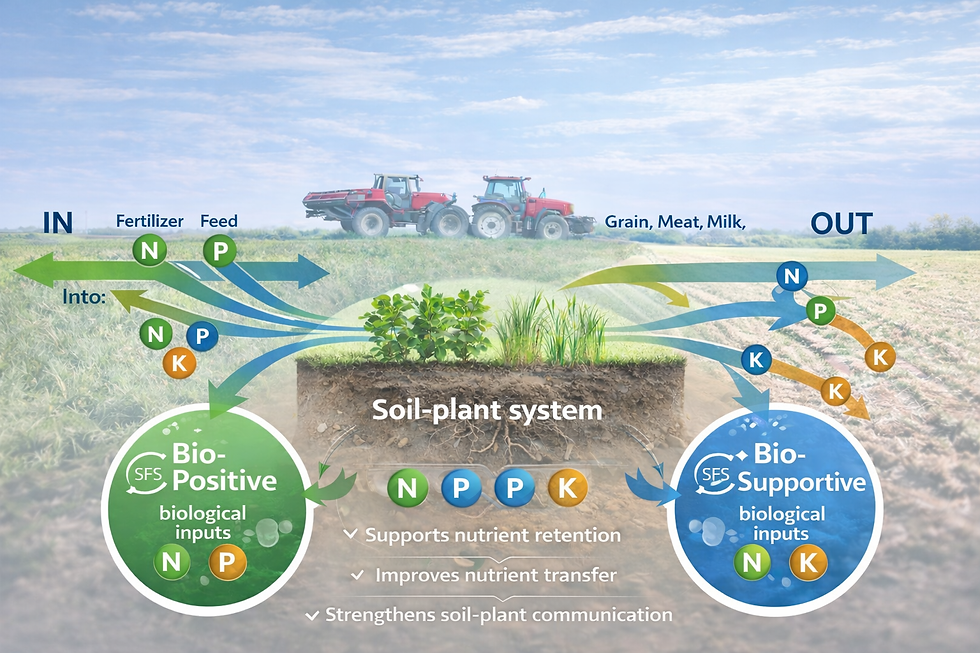

There is, however, a far better approach, and it doesn’t require ideology or dramatic changes. The principle is simple: healthier plants come from balanced nutrition, and balanced nutrition begins with a functioning soil. A soil rich in humus holds nitrogen instead of losing it. A soil with active biological cycles steadily cycles nitrogen rather than dumping it all at once. A soil containing the right balance of sulphur, magnesium, potassium and trace elements allows the plant to actually use the nitrogen it receives, rather than becoming swollen and brittle.

The reason all of this matters, especially now, is that agriculture is moving into a period where margins are tight, weather patterns are unstable, and input prices are unpredictable. Some farms will cope with this far better than others, and the difference usually comes down to soil function. Farms with carbon-rich, biologically active soils can achieve more with the nitrogen they apply because the soil is doing half the work for them. Farms that rely solely on bags and tanks inevitably feel more pressure because their nitrogen has nowhere to go and no support.

None of this means abandoning fertiliser or pretending nitrogen isn’t essential. It simply means using it in a way that supports the crop rather than undermining it. When the soil holds nitrogen properly, when the supporting minerals are balanced, and when biology is active and fed, crops become naturally tougher, more resilient and more efficient. Pest pressure drops, yield becomes more consistent, and the whole system stabilises.

Good nitrogen management isn’t about applying less for the sake of it; it’s about putting nitrogen into a soil and crop that can actually use it. When we get that right, everything else falls into place.

If you would like to know how SFS could help you further, go to www.soilfertilityservices.co.uk

Comments